Student compares COVID-19 to the Spanish Flu

We’ve heard the saying ‘history can repeat itself.’ One area where this rings true is the pattern of pandemics throughout history. A plague in 1720, cholera in 1820, Spanish flu in 1918 through 1920 and lastly, the current coronavirus (COVID-19) in 2020. It’s not to say that these pandemics are all similar in severity or longevity, or in biological makeup, but it goes to show that the situation we’re in now is not the first of its kind, and it definitely won’t be the last. Instead of this fact bringing fear into our lives, maybe it can bring comfort. Because after every period of destruction, humanity has survived. Maybe it would help if we connect to the past to help us navigate how to respond and live in the present/future. With this goal in mind, I’m going to compare the experiences of Americans and Austinites, if I can, during the Spanish flu with COVID-19.

“Even with all of our technology and smarts we have going for us today, I’m not sure we’re reacting much differently than they did in 1918,” said Stan Deaton, senior historian at the Georgia Historical Society. “It’s difficult to get people to give up freedom and community.”

How do some stats, hotspots, facts about the viruses compare?

Fun fact: The Spanish flu is only called that because Spain was the first place to report on it. The country was neutral during World War I, so it was not as preoccupied with other political stories to look into the disease.

Had to put that in because I was curious — now back to the story. Regarding the spread of each virus, the Spanish flu started in Fort Riley, Kansas in the U.S and was believed to have spread initially from rat fleas to soldiers in the trenches. When returning home from the Great War, they spread it to their families. As for the origin of COVID-19, it is believed to have been found first in bats, and the first cases in the U.S were in Snohomish County, Washington. In both pandemics, New York — and other upper east coast clusters — were especially hit by the virus because of the travel in and out of culture and business hotspots. This makes sense due to the influx of tourists, immigrants and business goers that travel in and out of the state

What was the experience of the medical world at the time?

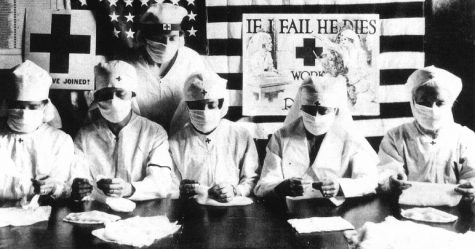

In Austin and the rest of America, healthcare workers and essential business employees are the highlighted heroes of this era. For example, a coalition of 100 Austin-area doctors helped to set up a system for efficient communication with clinicians and make sure that those who test positive for the virus but aren’t in need of hospitalization have a place to quarantine themselves for the health of their family — think the Austin Convention Center, hotels, etc. Issues that the medical world is experiencing is a lack of equipment such as ventilators and personal protective equipment, how to best prevent healthcare workers from contracting COVID-19 and the large number of cases in nursing homes. On the bright side, there are new developments such as TeleHealth to connect doctors to their patients that are quarantining.

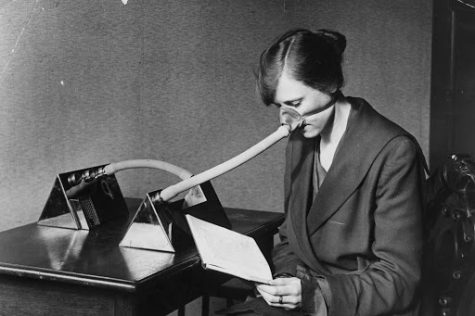

Similar to COVID-19, there were no flu vaccines to prevent the virus from taking root in the 1800’s and early 1900’s. In contrast, however, there were no antiviral medications that could help lessen the symptoms or diagnostic tests to confirm infection. Instead, healthcare workers would focus on recommending pharmaceutical remedies such as aspirin, Bovril (a thick, salty meat substance), turpentine, quinine, etc. Some even advised the exposure to fresh air and sun as a way to get rid of the influenza. Similar to now, the medical-equipment-to-patient ratio was unequal, and replacements for doctors and nurses who became sick were few and far between. Luckily and maybe consequently, the vaccines, ventilators and precautionary practices have improved dramatically with time.

How did the government, or state representatives, respond to the virus?

During both pandemics, quarantine or shelter-in-place restrictions were enforced. Wearing masks and the infamous social distancing proved to be helpful as well. Shortly after cases of influenza popped up in Philadelphia in 1918 a case was reported in St. Louis. The difference is how quickly and diligently both cities addressed it. Philadelphia had confirmed cases and then held a 200,000 person festival following the report. Likewise, St. Louis banned public gatherings two days after the first reported case and quarantined victims in their homes. In the end, the death toll in St. Louis was estimated to be about 358 people per 100,000 compared to 748 per 100,000 in Philadelphia during the first six months, according to the National Geographic article How some cities ‘flattened the curve’ during the 1918 flu pandemic. For the sake of avoiding the political conversations, here are some debates that both time periods argued about:

- Whether to reopen the country based on the welfare of the economy or to reopen when medical experts say it is safe

- How long, or if at all, schools, movie theatres or non-essential businesses should be closed.

- If canceling large gatherings is necessary. An example that comes to mind is the canceling of South by Southwest here in Austin. Although a different genre, The Stanley Cup Final, the world hockey championship, was canceled during the Spanish Flu.

How did people stay connected while keeping their distance?

Try to fathom no Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok or Facebook. Let’s even take the phone away. The TV and the iPad too. Maybe you have a radio. That doesn’t even cover the amount of connection that was stripped from those in quarantine in 1918-20. The drudgery of talking to the same family members or friends that we may feel now compared to only having a diary to write in or a face to glance at through a window. It’s not all different, though. Back then, when school was canceled, everyone cheered at the thought of not having to do work and thanked the virus for giving them freedom. That circumstance almost reminds me of when school let out for spring break, and everyone felt as if quarantine could be an extended vacation.

From that point forward, how people handled loneliness is what sets these two times apart. Or I should say the amount of entertainment and technology people had at their disposal. Today, people can still see their classmates and even have sports practices via Zoom; we have utilized technology to keep our community strong. We may feel lonely, and I know this is weird to hear, and maybe cliche, but we’re lonely together.

The only evidence of something close to inspiring initiatives like John Krasinski’s Some Good News segment or sewing masks to give to hospitals happening in 1918 was tying a white scarf on the door. Houses with infected people inside would tie a scarf on the door to warn others not to come near them. Their connection to the outside world only extended as far as to say, “Don’t come near me.”One fact is clear: when someone googles the title ‘Spanish flu stories of inspiration,’ what will most likely pop up is the death toll and the toll on the psyche of that generation.

How do the two pandemics compare in the negative response, or doing the contrary to what’s suggested, to the virus occurring at the time?

With that said, there were still people who did not take social distancing seriously or any of the precautionary guidelines during the Spanish flu or the coronavirus. COVID-19 hit the U.S at the time when spring break lets out, the weather is perfect for a Disney cruise and everyone is ansty for a vacation. In March, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) said that 20% of patients infected with the coronavirus were between the ages 20-44. Despite this, young spring breakers still went on trips, where they were up against hundreds of other people for a week, and contracted the virus. One such beachgoer, Brady Sluder, was interviewed in Fort. Lauderdale in March about his opinions on social distancing.

“If I get corona, I get corona. I’m not going to let it stop me from partying,”

22-year-old Sluder reportedly said.

A few weeks after that, that comment went viral. He then apologized and stated that he respected his family members, who are especially at risk, too much to keep ignoring social distancing warnings.

There is a lot of this mentality that young people are invincible, and this virus is a hoax. Some people are more careful, and even paranoid, about it. Maybe that’s because people weren’t as exposed to the coronavirus in the early stages, and because of that they didn’t take it seriously.

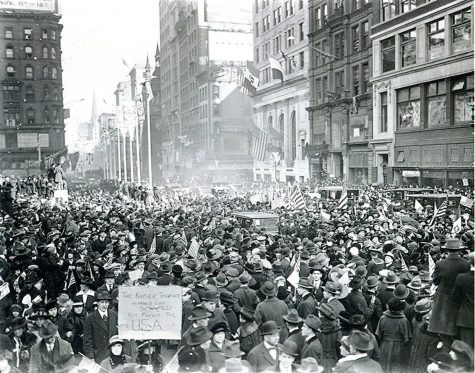

Similarly, a century before, Charlie Chaplin fans poured onto the streets of New York and crowded into the movie theatres to see Shoulder Arms. The manager, Harold Edel, of the cinema congratulated the success and attributed the moviegoers. “We think it a most wonderful appreciation of Shoulder Arms that people should veritably take their lives in their hands to see it,” Edel said during the uproar. Edel himself had died of the Spanish flu before this statement made it to press.

There’s a continuity here. In both eras, people are finding it difficult to self-isolate and stay in quarantine for months. There’s also an observation that civilians felt, and currently feel, as if by listening to medical professionals and being told to shelter-in-place, they are not in control of their lives. Denying that the virus is real, panicking on having to adapt to “the new normal” and recognizing mistrust in the leaders who are debating how to handle the situation are all apparent.

What role did the news/media play in the respective pandemics? How did the population respond?

I hope it’s not just me, but the 1918 influenza is rarely talked about, and I’m only learning about it now as I research for this article. According to Janice Hume, author of The Forgotten 1918 Influenza Epidemic and Press Portrayal of Public Anxiety, this is no coincidence. As the public eye was warming up to mass media, such as “national magazines and urban newspapers,” at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, collective knowledge, and with it, anxiety was forming. Connectivity was accompanied by skepticism towards the validity of Americans’ statements that, according to them, were completely true. At the start of the pandemic in September of 1918, the Literary Digest informed readers that “usually crisis has occurred after two or three days, with rapid and complete recovery” and that this disease would not cause any “serious consequences to the young and healthy.”

As time passed, and it was evident that this disease was more contagious than previously thought, the media played a big part in communicating regulations. The American public health agencies wanted to educate the population through programs on hygiene guidelines like the danger of coughing, sneezing and what was phrased as “the careless disposal of nasal discharges.” They also strongly advised hand washing before meals as prevention. If sleeping in the same bed, they encouraged something called “head to foot” sleeping, people laying with their heads on opposite ends of the bed.

Later in October of that year, news platforms like The Independent, The Survey and Literary Digest started describing it as an “enemy” that’s “stalking through the nation” and is taking a “ghastly” toll on the whole population. So, how did civilians respond to this sudden change in information about the virus?

As put in an article from The Atlantic, “when the perception of risk increases, the feeling of risk increases.” And because there were few sources and research available to confirm the status of the Spanish flu, it led to distrust in the media, the community and in some cases mass hysteria. Mass hysteria is a phenomenon of illusions of threats, real or imaginary, that spread through a group in society as a result of rumors and fear. It’s a fascinating debate: whether to tell the readers what they want to hear, good news, or whether to tell them the truth, even if it means admitting to the unknown and causing fear. But only telling the audience what they want to hear can also result in a blasé approach to a serious subject. With that said, the newspapers or radios beforehand may not be able to know the effect of the flu or its severity until it hits, so hoping for the best is maybe all they could’ve done. But telling them just how bad the circumstances are also creates a disconnect and paranoia between civilians.

As for the coronavirus, the uncertainty of what this virus is or how to cure it is still there, but now there are now more outlets to spread information through. That can be good or bad. Maybe the multiple sources’ different opinions can cause more confusion for the audience. On Nickelodeon, similar to the hand washing demonstrations mentioned above, clips of “SpongeBob SquarePants” teaching the audience how to thoroughly wash their hands are playing on TV. It is also well-known to practice social distancing and staying the recommended 6 feet apart, but other practices like touching elbows instead of shaking hands are popular.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that we have yet to understand the coronavirus completely, these aren’t as “unprecedented times” as we may think. There are patterns that have already been discussed and techniques that have gone through the trial and error process. Looking back, we can contemplate what worked and what didn’t and make our own assumptions of what’s best for wellbeing right now. It’s up for interpretation and exploration! We can learn from our past to appreciate the present technology and medicine that we have and make our future infinitely better.

To learn more about the 1918 pandemic virus click here.

To learn about the changes coronavirus will make to our futures click here.

To learn about the misconceptions of the Spanish Flu click here.