My older sister is sort of the perfect grades girl, and growing up with that hanging over my head taught me that some stereotypes, even ones that can be considered as “positive,” can feel more like bars — especially when you’re Indian. Everyone just assumes academic brilliance runs in your DNA.

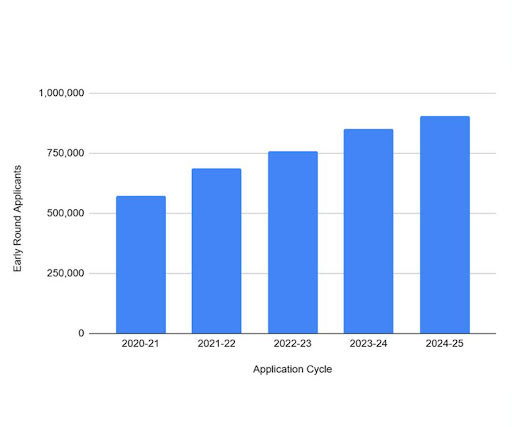

She got the grades that every parent dreamed that their kids would get — pristine 100s, even in some of the hardest APs. She was in the top 10% and had a work ethic some would kill for. Now she’s a sophomore at Boston University — a school with a 12% acceptance rate — studying math and physics. To an extent, she’s basically living proof that the stereotypes about Indian kids and STEM subjects can actually come true.

Meanwhile, here I am as a junior in high school, collecting solid mid-90s in some of the same classes as her, and I’m wondering why the same genes that made math a walk in the park for her decided to skip over me.

Everyone knows the stereotype. Indian kids are supposed to be academic masterminds. We’re expected to excel specifically in STEM subjects, have our college plans mapped out before we even hit high school and end up being an engineer or a doctor. It’s a stereotype that seems like a compliment on the surface — who wouldn’t want people to assume you’re smart? — but if you don’t naturally fit that mold, then it becomes suffocating.

The pressure in my house is real and constant. My parents, both engineers, both made it to the US — the Indian dream, and they both graduated from top universities. They look at her success and see proof of what’s possible and what should be possible for both their daughters.

“You have so much potential,” they tell me after every near-perfect test score.

“You could get 100s if you just applied yourself.”

“You’re right there, just bordering on the edge.”

“You just need some more practice. Practice. Practice.”

If only I could tell you how many times I’ve been told that practicing would fix all my problems. They don’t mean to hurt me; they just want what’s best for me, what’s going to help me succeed the farthest. Yet sometimes when I get a 94 on a chemistry test, and it’s met with questions about what went wrong with those missing few points, that 94 feels almost like disappointment.

The comparison to my sister is inevitable and constant. She’s flourishing at Boston University, probably solving complex equations while I’m here struggling to care about the values of the unit circle. My parents have never outright said it, but I can feel their disappointment when they talk to their friends about their daughters — one studying math and physics at BU, the other… still figuring out how to study.

What might be even worse is that my sister has never made me feel like something less. When she comes home from school on her breaks, she listens to me talk about how hard school is without telling me that if she could do it, then I can too. If I ask for it, she would help with my math or chemistry homework without being condescending. She used to talk to me about the types of people she was being surrounded by, just because of the advanced classes she used to take. She also feels certain expectations at BU, but she has also admitted that she can’t imagine doing anything else — numbers and equations just make sense to her in a way they never have to me.

But the one thing I have started to understand is that the cornerstone of Indian excellence — this whole thing of having incredible brains — that’s meant to act as an uplifter, is actually an incredibly limiting point of view. I have lived in India, and for three years of my life, I did my schooling there. I don’t believe I can put it into words just how different the schooling is. It’s like going from handheld on-level chemistry to AP organic; completely unpredictable — they work to push every single student beyond their capabilities. The goal is simple: get to the U.S — they still believe the propaganda of the land of opportunity — and make a name for yourself. The stereotype assumes that we all want the same things to strive for nothing but perfection. They think that everyone has the same narrow definition of success; by assuming we all also believe that if you get a 95 instead of a 100, you simply didn’t try hard enough.

But that’s not true for everyone. Sure, you’ll find those people who see that they got a 99 and think they’re a failure for missing that 1 point. But the fact is that just because you’re from this one certain place doesn’t mean you’re all destined for the same path, even if they share blood. Some will go into theoretical physics, others into fieldwork or conservation. Some will naturally get that perfect score, others are going to push till they can’t get them, and the rest are going to pursue what they actually care about. We’re not a monolith, and our worth shouldn’t be measured against a single standard of achievement.

I’m still working to figure out how to navigate the expectations that my parents have for me without bending over backwards and killing myself to do it. I know they love me and want me to succeed, but I wish they could see that success might look different for me. Maybe I won’t be a prodigy studying at an elite university, but I could be on another path working to make a huge change — and it could possibly be just as valuable.