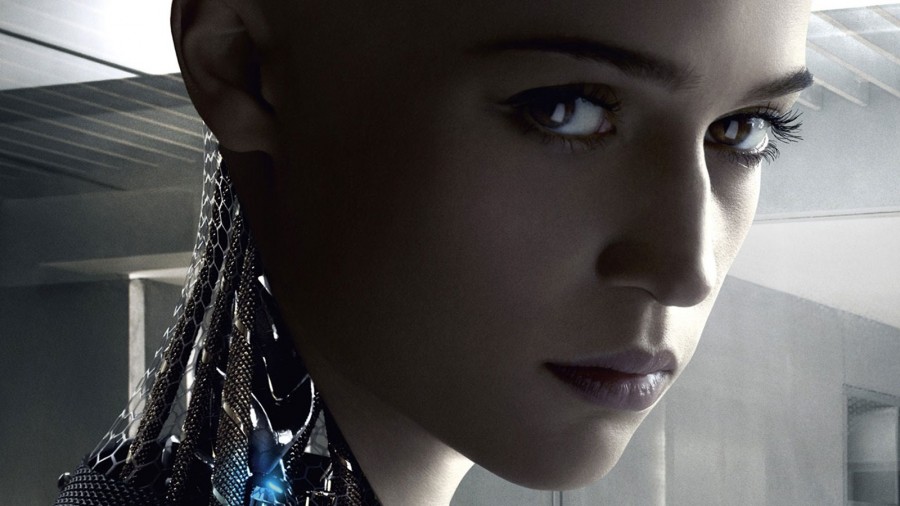

In Ex Machina, artificial intelligence provokes thought, thrills

To a generation of kids growing up on Star Wars and Star Trek nerdery, space may have sufficed as “the final frontier.” But millennials spend a lot less time looking up at the stars and instead look down at their laps, where smartphones are stashed. Science fiction for today’s audience is gravitating in a different direction, and focus is shifting away from intergalactic action towards technological thrillers. One sub-genre, concerned with theories of artificial intelligence, is perhaps the most haunting manifestation of this new trend.

Ex Machina is just the latest film in recent years to explore the idea of AI. In many ways reminiscent of Spike Jonze’s 2013 robot-love-story Her, writer and director Alex Garland’s portrayal of human-tech interaction is harsher, if not necessarily more cynical. In Her, the question is not whether computer operating system Samantha is intelligent, but whether this man-made intelligence is capable of human love — quite a romantic concept. In Ex Machina, the intelligence of a subtly seductive fembot is still in question, and love only serves to cloud how humans judge her faculties — an approach that is somewhat more chilling.

Caleb is a capable computer programmer at Bluebook, a search engine company similar to Google, and in the opening scene of the film wins a weeklong trip to his employer’s vast and futuristic estate. He does not know what to expect when he meets enigmatic Bluebook CEO Nathan (a fantastic Oscar Isaac) and enters his tricked-out home, but the two tech dudes quickly cut short their bro session and get down to the real business: Caleb is to perform a Turing test on Ava, Nathan’s AI creation, in which he attempts to distinguish whether her answers to his probing questions are truly independent thought, or merely advanced programming.

In a traditional Turing test, the questioner does not know whether they are speaking to a human or a computer. Because Caleb is aware that Ava is a robot, the complexity of the test is heightened. He discovers the challenge of distinguishing the human emotions that Ava appears to be experiencing from the emotions he may be projecting onto her as his fascination and attachment grow. Likewise, his mind must stay open to the possibility that Ava might actually be truly intelligent. This struggle is the cornerstone of the film, a mind-bending exploration of intellect and autonomy, pockmarked by manipulation, sexuality and the cognitive trap of man’s ego.

Unfortunately, the promising premise fails to deliver any real bang. All the elements are there, but the film itself is just too predictable. The questions it raises are indeed complicated, yet their answers are revealed too early and too obviously; no one will be left surprised or confused at its conclusion. While this does not have to be a flaw, it becomes one in Ex Machina simply because the movie bills itself as a thriller but is more valuable as a discussion.

The philosophical banter and advanced tech specifics which dominate much of the screenplay are at least somewhat balanced by the psychological tension that begins to grasp the audience when cameras move below Nathan’s minimalist mansion, into a windowless, underground research facility where ominous power outages are all-too-frequent. The central trio of Nathan, Caleb and Ava exist in a fishbowl of sorts, and a growing sense of isolation and imprisonment do plenty to create a bleak mood — but not enough to convince an audience that what is coming is catastrophic. Ex Machina successfully addresses plenty of the confusions humans harbor about artificial intelligence. What it lacks is the energy to turn these confusions into fears.