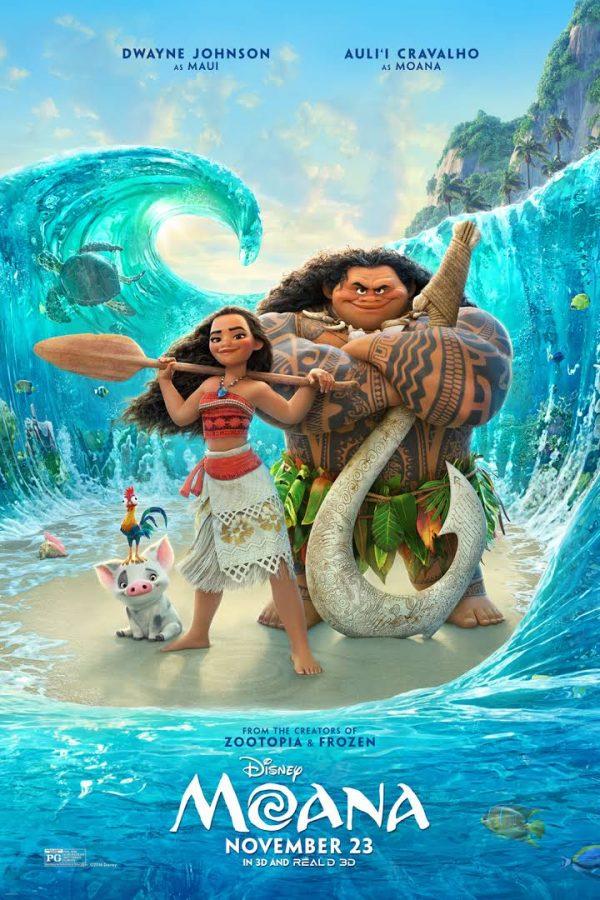

Disney’s Moana means more than just a box office hit

Disney’s newest film, Moana, is perhaps the powerhouse’s best animated feature yet.

Set around two thousand years ago in the Polynesian islands, following our heroine, Moana, on her quest to save her people, the movie is, quite simply, my favorite concoction of Disney magic yet. Moana is headstrong and brave, next in line to lead the people of her island as the village chief. It’s a duty she’s ready to accept — be it not for the fact that Moana has been chosen by the ocean (who, in this tale, is a sentient being) to restore the heart of Te Fiti, the Polynesian island goddess.

Together with the larger than life demigod Maui, Moana sets out on an adventure to save both Te Fiti and her people. It’s a heartwarming tale with a twist on the typical Disney adventure storyline — one that has the makings to be a classic among the ranks of famous Disney movies like Beauty and the Beast or Aladdin.

Disney has managed to make this movie so beautifully, culturally rich, teeming with life, action and color. The sheer beauty of the movie is in the animation — down to details like the movement of clear blue waters, golden sunsets, even the character’s hair (which might as well be a character in and of itself, with how touchable and realistic it appears). The animation of Moana speaks volumes for how far CGI has come, even just in the last five years. The casual and constant flow of movement in the visuals of this movie — Moana throwing her wet hair into a bun, Maui’s tattoos that quite literally come alive, trees rippling in the breeze — speak for both the production value and the hard work involved with a movie that has been in the works for around five years.

But even the incredible visuals cannot eclipse the most important aspect of this film: that for the duration of the movie, the lead is a character with brown skin, dark eyes and hair, non-white features, and a realistically proportioned body. Our hero of the film is a princess of color, and that means something to people like myself, because representation matters. Thousands of little girls will get to see a character who looks like them saving the day. It’ll matter to them too.

The film also shines musically. The songs simultaneously lead the plot along while maintaining the catchy, earworm-y quality of Disney’s most popular songs (such as Frozen’s “Let It Go”), full of deeper messages and belted high notes.

The movie’s soundtrack was primarily written by the increasingly popular Lin Manuel Miranda (the mastermind behind the groundbreaking Broadway musical Hamilton), and it is Miranda’s quirky writing style and distinct sound that helps to set Moana apart. No two songs are alike, a refreshing twist on the Disney’s typical formula for a soundtrack. There’s a song with a rap in it, a song in the musical stylings of the late David Bowie, and even several songs sung in Polynesian, as Moana is, at its core, a story about the Pacific Islands and their mythology.

But despite music strong enough to carry an entire film, Moana doesn’t just rely on its songs to tell its tale.

Moana is a movie that teems with life, from its visuals, to its music, to its well-rounded, three-dimensional characters and their voice actors. Moana, our protagonist, voiced by newcomer Auli’i Cravalho, is strong and brave, stubborn to a fault, and curious. She is endlessly relatable, not just through her lines and attitude, but through her mannerisms as well. Meanwhile, Maui, the demigod whose help Moana enlists, voiced by Dwayne Johnson, provides most of the film’s comedic relief through his enormous ego and antics, while still managing to have an emotional backstory and transformative character arc.

Because the movie’s target audience is families, the movie’s humor ranges from physical comedy to current cultural references, and is funny to all, not just little kids.

There is a slight adherence to Disney’s formula of the Hero’s Journey, but that exact formula exists because people continue to fall in love with it again and again in all its forms. Particularly now, with our country so racked with fear and uncertainty following this election, the archetypes that this film possesses are more comforting than annoying, providing gentle reassurance and uplifting us from the chaos of life.

One of the most important, crucial aspects of Moana — at least for me — is that her capability to lead her people as the next village chief is never, ever doubted by anyone but herself. There is no discussion of her needing to be married before becoming chief, no suggestions that perhaps a woman isn’t skilled to lead the village, no hints of her parents wanting a male heir but having to settle for a girl. Moana is raised from birth told she is going to be the next leader of her village, and every single one of her people believes in her, has faith in her strength and tenacity, never doubting her abilities. Moana wants to lead her tribe, does not run from the responsibility or wish she were someone else (Elsa, Ariel, I could go for a while). When she leaves on her Hero’s journey, it’s to save her people.

I know it sounds like I’m making a big deal out of a small portion of the movie, but that’s because to me, this is a big deal.

A typical movie formula with a female heroine often centers around the doubt those around her place in her abilities (In Princess and the Frog, no one believes in Tiana being able to start her own restaurant, in Mulan she is not allowed to take her father’s place in the army until she disguises herself as a man, and so on, and so on). Of course, the main character gets to prove them wrong, but the thing that has always bothered me is that we as women shouldn’t have to fill requirements to prove we are worthy of respect. It should just be assumed, unconditional, that women are just as qualified as their male counterparts.

I thought about this on the car ride home from the movie, and promptly burst into tears. My friends couldn’t understand my tears and at the time, I couldn’t put it into words either.

I cried because so many people around me still accept this stereotype that men are natural leaders, strong and intelligent, allowed to be flawed and selfish, while women are better at nurturing, at being soft and pliable, of apologizing and stepping out of the way; that a woman has to prove herself worthy to even stand on the same level as a man does by doing nothing.

I was crying because it is so tiring to constantly have to prove yourself as being worthy of being taken seriously and watching your male classmates never meet that obstacle. I cried because people assuming that you will inevitably come in second — that you would be happy to come in second, lucky, even — makes it so hard for you to even believe in yourself.

Moana’s story isn’t about proving herself to her people. At the end of the day, I think Moana is a love story. Not one centered about romance, to be sure, but to me, it is a love story nonetheless.

It’s a love story about finding your own identity — both in the context of who you are inside and who life’s responsibilities need you to be. It is about how it is OK to need help — to draw our strength and our courage from the people we love, and to love and help them in return. Most importantly, it is embracing the person we know ourselves to be: the good along with the bad, our successes and our failures.

Moana is a love story to me because most people (particularly women) are never able to find that kind of self love, to achieve that ultimate acceptance of themselves as they are outside of the scope of others’ opinions and perception of us.

Moana may be just a movie, but can anyone really blame me for wishing it was real?